In today’s world, women are still punished for being too loud, too emotional, too much, not enough, constantly living up to unebelievably impossible standards. Women as a whole are up against generational and patriarchal systems that have never stopped trying to exploit and abuse. So when I started writing Shadows in Dream Stone, I wrote with a feminine rage that would capture those injustices.

Four years ago, the ideas for Shadows in Dream Stone was conceived on a drive home from the store with my mom. We’d just learned Texas had overturned Roe v. Wade, and furious will always fall short of how we felt about it all. And since then, attacks on women only seem to be getting worse.

After roughly outlining the story in my head, I set out to write an angry novel driven by a character who felt there was no other option but a path of vengeance. As I continued writing, I realized I wasn’t just writing about the survival of this very real, flawed, and tormented character. I was also writing about the alchemy between rage, resilience, and rising up.

That is what women’s stories are: a collision of all that is is taken from us and the courage we still have to create anyway.

Why Do We Read Dystopian Fiction?

As I come close to publishing Shadows in Dream, I’ve asked myself why anyone would want to read about this woman’s story, her darkness, her trauma, and what she has to go through to save women and herself. Who would want to endure her pain and why?

Works of dystopian fiction give us space to breathe and resonate with the troubles around us. And in terms of the feminine rage women feel, it gives us a chance to speak in shouting opposition of the violence happening against us. It gives us a chance to ask the question, “What does freedom look like when every part of me has been told I don’t deserve it?”

Shadows in Dream Stone deeply explores this world and, similar Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale contains moments that have already happened somewhere in our past and current timeline. And as the Huffington Post says:

“Sometimes, authors of dystopian literature temporarily ease the tension a bit with humor, as the great Atwood does with some of the clever genetic-engineering terms she coined for Oryx and Crake. And dystopian books can have seemingly utopian elements — with things not appearing too bad even though they are bad; Brave New World is a perfect example. There are even novels, such as The Shape of Things to Come, that mix dystopian and actual utopian elements.”

We love dystopian novels and all the violence, despair, and injustices in them because they include characters we’re drawn to. Characters we can relate to. In a way, dystopian novels also provide a worst-case scenario that helps us be more observant of the world around us.

Why Female Rage Matters in Dystopian Fiction

In a world that still tries to silence women’s voices, writing about female rage isn’t just dramatic—it’s essential. Dystopian fiction gives us the mirror to see how systemic cruelty, emotional suppression, and hidden fury shape lives and, in turn, how characters reclaim voice and power.

Here are three lenses through which this matters: societal emotion norms, gendered storytelling dynamics, and the urgency for representation.

1. Societal Emotion Norms & Women’s Rage

Anger is often stigmatized in women. Recent research shows that women’s experiences of anger evolve in ways that reflect both internalization and repression.

A 2025 study of more than 500 women aged 35–55 found that although forms of anger (temperament, reaction, aggressive expression) decrease with age, feelings of anger still increase in midlife while outward expression is suppressed.

Another 2025 study on “mental load” revealed that women, particularly those who are college-educated and employed, carry significantly more emotional and cognitive labor in both domestic and professional settings, leading to higher emotional fatigue.

These findings matter for fiction because when you place a woman in a world that punishes emotion, that erasure of outward rage becomes its own form of violence. That’s the terrain of characters like Abaddon Ordell. The rage unspoken becomes the spark of revolt and in her character, we see ourselves a little bit more.

2. Gendered Storytelling Dynamics & Representation

While the story of “Shadows in Dream Stone” is futuristic and speculative, its roots are centuries deep. Research tracing fiction from the 19th century onward shows that women’s emotional lives have long been filtered through male perspectives.

A 2024 study found that novels written from a male point of view “systematically objectify female characters.” Another found that a “gender agency gap” persists even into the 21st century, with women characters still more likely to be portrayed as passive in cross-gender dynamics.

Even though fiction is changing, those narrative imprints linger. Readers have been trained—often unconsciously—to see women’s stories through male frameworks: her pain as aesthetic, her silence as virtue, her fury as threat.

When a story like Shadows in Dream Stone centers a woman’s rage not as spectacle but as truth, it rewrites the code. It reminds us that female anger is not chaos but clarity.

3. Rage as Revolution

Feminist dystopian fiction remains vital and reclaims the emotional landscape history once edited out. It says: You were never too much; the world was simply too small for what you carry.

In stories like Abaddon’s, rage becomes a data point of the soul. It is evidence of empathy unreciprocated, of care turned inward until it combusts. It’s not destruction for its own sake. It’s a rebellion of feeling, a refusal to remain invisible, and a mirror held up to every system that demanded women keep smiling through the ache.

Because female rage, when written with heart, isn’t about fire. It’s about light.

The Balance Between Rage and Resilience

Rage isn’t the opposite of resilience. It’s often where resilience begins.

A 2023 meta-analysis found that women self-report lower resilience than men, a difference researchers link to chronic stress, unequal emotional labor, and social pressure to stay composed. But data like that doesn’t mean women are less resilient. It means the system measures resilience in silence—rewarding stoicism, not endurance.

Because in truth, women’s lives are built on resilience that’s rarely acknowledged: raising children, healing through loss, surviving inequity, creating beauty from fracture. That’s not fragility; that’s power in motion.

In Shadows in Dream Stone, Abaddon’s rage doesn’t destroy her. Instead, it steadies her. It’s the first spark of recovery, the moment she stops apologizing for her own strength. Real-world research reminds us that women’s resilience grows strongest where community and meaning take root, not where they’re told to “stay calm”.

Resilience isn’t quiet recovery. It’s rebuilding in full voice—rage as spark, softness as strength, and survival as a form of art.

Writing Emotion That Feels Real

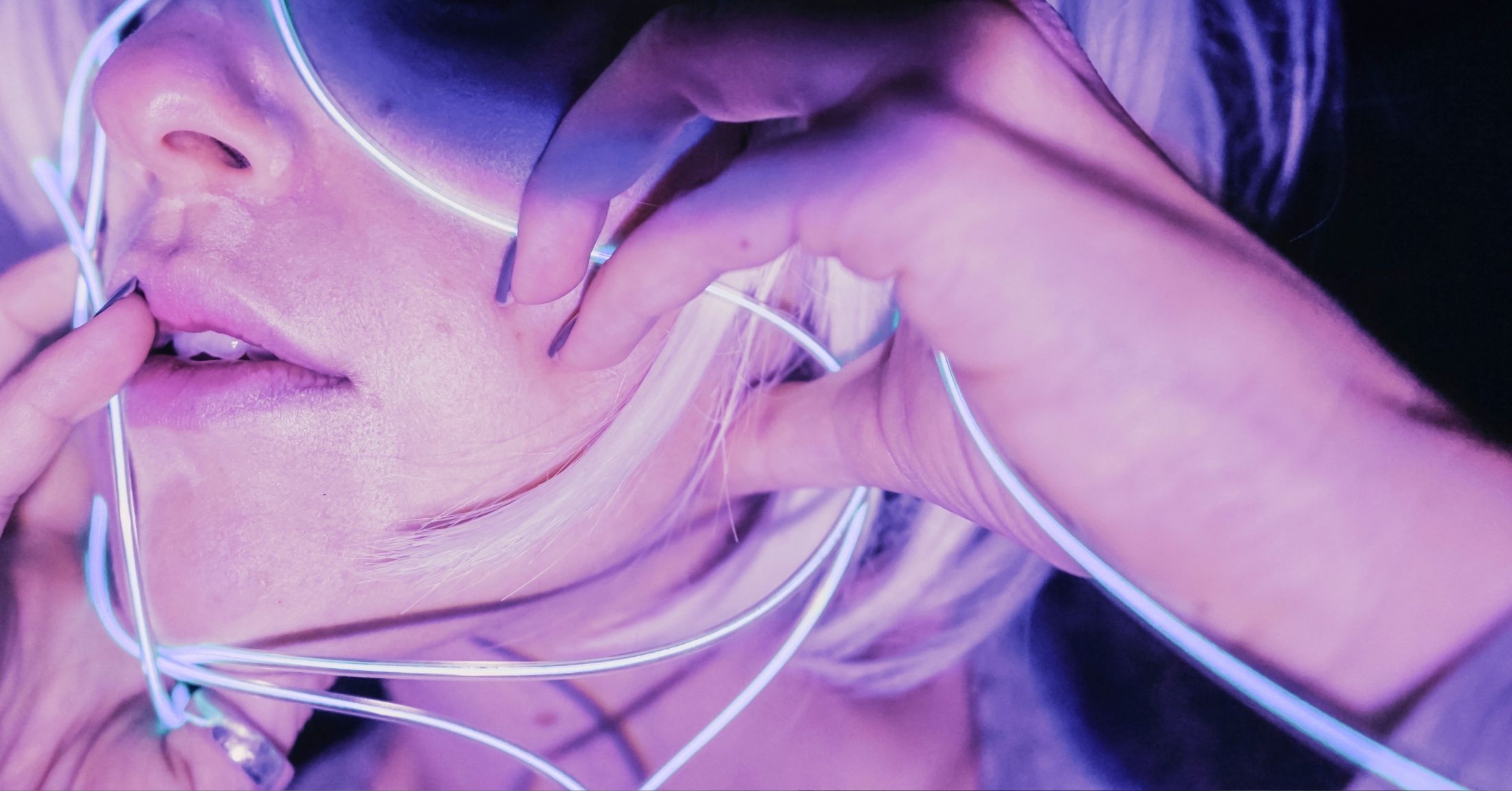

It mattered to me that Abaddon felt real. Not the polished kind of real we see on book covers or in movie heroines, but the kind that flinches, rages, and aches her way through the world. I wanted her to carry the same fire I see in women every day. The ones who are furious because they’ve been told to endure, who are tired of waiting for justice that never seems to arrive.

I’ve always loved writing characters who are both vulnerable and angry, because I often feel that way too—torn between the part of me that wants to believe the world is good and the part that knows how cruel it can be. Writing Abaddon was a way of saying: both can exist. You can be soft and furious, broken and brave, grieving and still good.

More than anything, I wanted people to see that even in their flaws and traumas, women like her—like us—are still completely lovable and deeply capable of love. We don’t need to be healed to be worthy. We don’t need to be gentle to deserve grace. Sometimes the most human thing we can do is let ourselves be seen in all our contradictions—angry, tender, hopeful, undone—and trust that someone will still choose to stay.

Because that’s what makes emotion real: not perfection, but permission.

Shadows in Dream Stone: Rage as Revelation

Rage gets a bad reputation, like it’s something we have to tame or outgrow. But in truth, rage is revelation. It’s the moment we finally see what has been hurting us and refuse to look away.

When I wrote Shadows in Dream Stone, I realized Abaddon’s anger wasn’t just a reaction to injustice. It was the light by which she began to see herself clearly. Rage gave her language. It gave her boundaries. It gave her back her name.

That’s what I want readers to feel, too: that rage doesn’t make you unkind or unlovable. It means your heart is still alive enough to notice what’s wrong. It’s the pulse that says, I still care enough to want better.

In every woman I know, there’s a version of Abaddon—a quiet storm of compassion and exhaustion, of love that’s carried the weight of too many worlds. Rage is not what destroys her. It’s what wakes her up.

Because beneath the fire, there’s always something sacred: the hope that things can still change, that we can still love, that the story isn’t over yet.